A review of Australian parliamentary drafting styles

Thank you to Toby for enabling my bad ideas (viz. writing this post), and thank you to COVID-19 for giving me the time to follow through.

As someone who winds up doing a lot of legal-adjacent1 drafting,2 I spend a fair amount of time staring at legal documents – most commonly, legislation from various Australian jurisdictions. Clearly, all those words rattling around in my head have knocked something loose, for I have developed some strong feelings on the matter of drafting – and it's time to let them loose on the world!

He who fights with monsters should look to it that he himself does not become a monster. And if you gaze long into an abyss, the abyss also gazes into you.

—Friedrich Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil, Aphorism 146

Before we begin, it of course needs to be said that there is little objectively ‘good’ or ‘bad’ about drafting practices. In the end, it does come down to a matter of taste.3

Federal

The federal Office of Parliamentary Counsel (OPC) ‘is responsible for drafting and publishing the laws of the Commonwealth of Australia’, and has a wealth of information on its drafting practices available on its website. I'd like to give special mention to the OPC's Plain English Manual, which is an excellent guide on the use of plain language in legal materials.

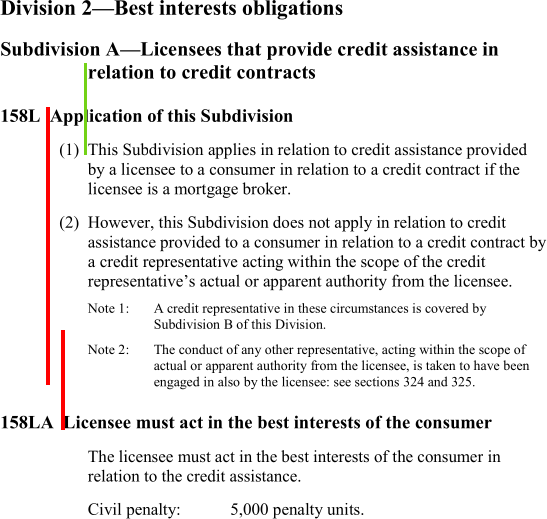

For this review, I present a recent piece of legislation, the Financial Sector Reform (Hayne Royal Commission Response—Protecting Consumers (2019 Measures)) Act 2020 (Cth) as an example of federal OPC style.4

Alignment

Federal OPC style is fairly nice. The alignment of paragraphs is neat, with section/subsection text indented relative to the left page border, and subsection numbers located within that marginal space. This creates pleasing, clean vertical edges:

This alignment, however, does not extend to section headings. Section numbers are separated from titles by a fixed space, and titles therefore do not line up when section numbers are of different lengths:

This is most unappealing! The same extends to headings of larger units (such as Chapters, Parts and Divisions), though those numbers are separated from titles with em-dashes, so the lack of alignment is more forgiveable – and I do note that the hanging indent on those titles is pleasingly aligned with the section body text.

Punctuation

Note in the preceding images that text such as notes and penalty provisions are introduced with colons. The same is true of lists – also introduced with colons. Accordingly, lists that continue into further body text lead out with a semicolon:

List items are also separated by semicolons.

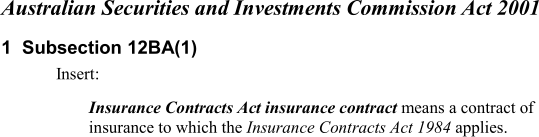

Amendments

In federal OPC style, amendments to legislation are set out in Schedules within amending acts. An ‘activating’ section is included to give effect to the amendments, which usually reads:

Legislation that is specified in a Schedule to this Act is amended or repealed as set out in the applicable items in the Schedule concerned, and any other item in a Schedule to this Act has effect according to its terms.

This is unfortunately a little wordy, but does have the advantage of greatly reducing the wordiness of the amending Schedules themselves:

Beautifully concise!

Miscellaneous

Federal OPC style renders the titles of other legislation being cited in italics. This earns the federal OPC extra style points, as italics are how we usually represent the titles of other works in non-legal contexts.

When cross-referencing provisions, federal OPC style names the provision by the smallest unit referenced (‘reverse referencing’). Therefore, for example, ‘paragraph 8(1)(a)’ refers to paragraph (a) of subsection (1) of section 8. While this does make sense (we are, after all, referring to a paragraph), this does create some small degree of difficulty actually locating a referenced provision, which I'll discuss in more detail shortly.

Victoria

On now to Victoria, the state where I currently live, where the Office of the Chief Parliamentary Counsel (OCPC) ‘drafts legislation for the government and the Parliament of Victoria’.

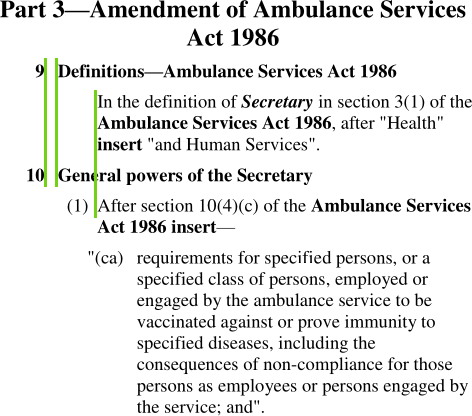

Here, I present the Health Services Amendment (Mandatory Vaccination of Healthcare Workers) Act 2020 (Vic) as a representative example.

Alignment

Victorian legislation is formatted similarly to federal legislation. As with the federal style, section and subsection text is nicely aligned, creating a neat left margin:

Note further, though, that the Victorian styling of section headings is leaps and bounds ahead of the federal style! Section numbers are flush right-aligned and offset at a fixed distance to the left-aligned section titles, creating pleasing alignment of both the section numbers and titles.

The Victorian style, like the federal style, uses em-dashes to separate numbers and titles of larger units, but centre aligns these, obviating any concerns about alignment of the numbers and titles.

Punctuation

As the preceding image shows, Victorian legislation, unlike federal legislation, prefers the em-dash to the colon when introducing lists and other matters.

On the one hand, this is a neat idea. It reinforces the idea that the list items flow on continuously from the lead in text to form a continuous sentence. It also avoids ending a list with the somewhat unusual-looking bare semicolon, the em-dash providing a stronger sense of ‘But wait, I'm not finished yet!’

On the other hand, though, the use of em-dashes in this way is a real ‘legalism’. Outside of legal contexts, when we want to introduce a list, we use colons, not em-dashes, and the continued use of em-dashes seems to run somewhat counter to increased focus on plain English drafting.

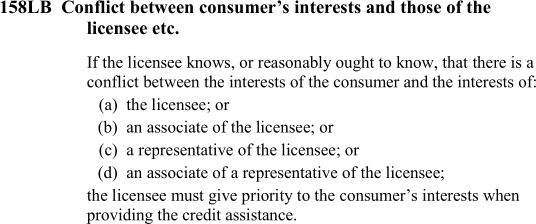

Amendments

The handling of amendments is where the Victorian style loses many style points. Victorian legislation does not separate amendments into Schedules, and instead presents them in the main body of the Act.

As the image shows, every amendment is therefore explicitly narrated, and each section accordingly repeats the name of the principal Act being amended.

This blows up the size of the text, and the use of the narrative style also somewhat obscures the effect of the amendment. In section 9, for example, one has to jump around a bit to locate the site of the amendment – first to the middle of the sentence to locate the Act, then backwards to find the section, then backwards again to the specific definition, before lurching forwards to identify the exact site.

Compare this with the federal OPC style, where the components would flow much more logically:

Ambulance Services Act 1986

9. Section 3(1) (definition of “secretary”)

After “Health”, insert:

However, the Victorian style does have the advantage of being able to use the clause heading to summarise what the amendment does.

Miscellaneous

Also unlike the federal style, Victorian legislation presents the names of cross-referenced legislation in boldface, rather than italic. This is simply bizarre. Outside of legal contexts, boldface is not used to identify titles, and even within legal contexts, it is arguably more commonly used to signpost definitions.

Why even boldface? – it is not as if the title of a piece of related legislation is an important feature that needs to be drawn attention to.

As the image shows, the Victorian habit of bolding the verb in an amending provision also creates the bizarre visual image, say, of ‘Ambulance Services Act 1986 insert’ all in boldface, as if ‘insert’ is also part of the title.

When cross-referencing provisions, Victorian style also stands in opposition to federal OPC style, referring to a provision by the largest unit referenced (‘forward referencing’). Therefore, paragraph (a) of subsection (1) of section 8 might be referred to as ‘paragraph (a)’, ‘subsection (1)(a)’ or ‘section 8(1)(a)’ (whereas it would be referred to as a ‘paragraph’ in all cases in the federal OPC style).

At first glance, this seems bizarre. After all, we are referring to a paragraph, not a section or subsection. But there is logic behind the madness. Conceptually, while the OPC style gives a name to the provision, the Victorian style tells us how to get there. In the case of ‘section 8(1)(a)’, we go to section 8, then look for the (1) subunit, then look for the (a) subunit. This assists readers in locating the provision.

Contrast this with the OPC style, where upon reading ‘paragraph 8(1)(a)’, the reader is expected to simply know, without any further guidance, that the ‘8’ refers to a section number. While this may seem trivial for someone familiar with legislation, legislation is written also for laypeople, who may not be familiar with the conventions of legislative subunits. For this reason, the Victorian style of cross-reference gets my endorsement.

South Australia

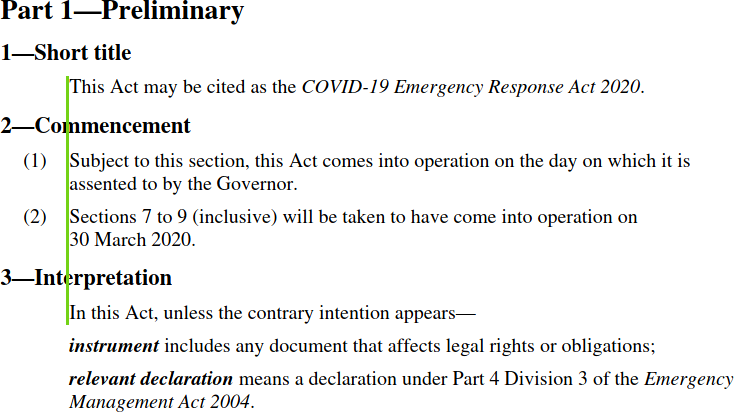

We turn now to my home state of South Australia, where legislation is drafted by the SA OPC.

As an example of the SA OPC style, I present the COVID-19 Emergency Response Act 2020 (SA).

Alignment

SA OPC style is again similar to the federal style, with section and subsection text nicely aligned:

Like the federal OPC style, section numbers are separated from section titles by a fixed distance (albeit by an em-dash rather than spaces – someone likes their dashes!), and so fail to align when the lengths of section numbers vary.

You may also note that the subsection numbers appear to be separated from the text by a greater margin – this is because the subsection numbers are centre aligned within the margin:

This is certainly an, err, ‘interesting’ choice.

Punctuation

South Australian legislation, like Victoria, introduces lists with the em-dash. Unlike Victoria, however, when a list contains lead out text, it is introduced not with a further em-dash but instead with a comma:

While I generally support the use of simpler, plainer punctuation (and a comma is certainly simpler than a semicolon or em-dash), this strikes me as simply inconsistent, especially considering semicolons continue to be used between list items.

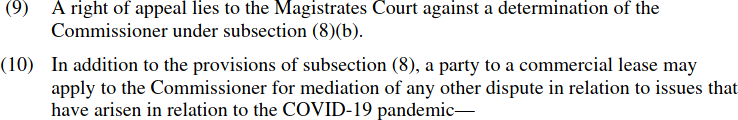

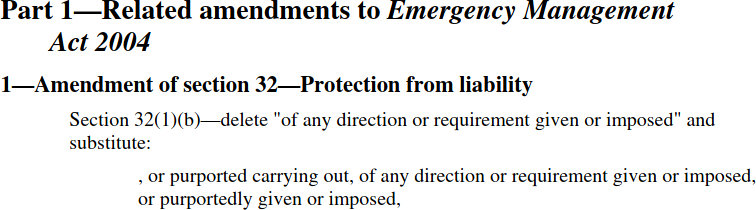

Amendments

South Australia follows the federal practice of having a global ‘activating’ section for amendments, which is more plainly worded, too, reading something like:

In this Act, a provision under a heading referring to the amendment of a specified Act amends the Act so specified.

However, South Australia mixes in a little of the Victorian style too, using the title of the clause/section to summarise the amendment, moving the pinpoint reference to the main text of the provision:

This approach probably combines the best of both the federal and Victorian approaches – allowing for more concise amending provisions, while also allowing headings to summarise their contents.

Miscellaneous

South Australian legislation, like the sensible federal approach, presents titles of legislation in italics, and like the superior Victorian approach, refers to cross-referenced provisions by the largest unit (‘forward referencing’).

New South Wales

Back to the east coast now with New South Wales. NSW is distinguished, of course, in that its legislation is drafted not by an Office of Parliamentary Counsel but instead by the Parliamentary Counsel's Office (PCO).

The NSW PCO is also the first state jurisdiction we've looked at to publish drafting guides online. While most of the NSW drafting practice documents are quite short and uninformative, I must commend their Gender Neutral Language Policy which, though squirreled away inside a large list of dot points, does recommend:

using “they”, “them” and “their” to refer to a singular noun

It is, of course, perfectly grammatical to use the singular ‘they’, and it has been in use for centuries. I keenly await for the federal OPC to follow suit in their drafting practices!

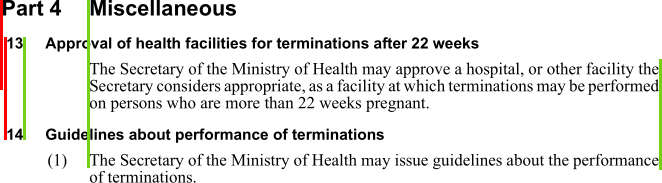

Back to the topic at hand, I present the Abortion Law Reform Act 2019 (NSW) as an example of PCO style.

Alignment

The PCO makes some nice looking legislation. As we've come to expect, section and subsection text is aligned, but the PCO goes even further, and is the first not to dodge the issue of Part heading alignment, with Part titles aligned neatly along that very same axis:

Not only that, but the PCO style gets bonus points for justifying the body text, resulting not only in neat left side margins, but also neat right side ones.

Additionally, as in the Victorian style, section numbers and titles are nicely aligned, though it pains me greatly to point out that this does not extend to Part numbers, which are mere pixels away from being perfectly aligned. (Pixels, I say!)

Punctuation

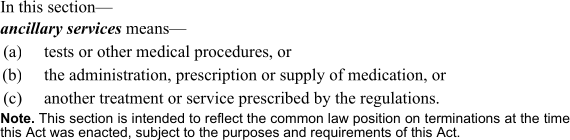

NSW legislation, like Victorian and South Australian legislation, leads into lists with an em-dash, but breaks from the pack by separating items with commas:

While I do disapprove of the em-dash as previously discussed, the use of commas is very pleasing to see.

Furthermore, NSW legislation does not use the em-dash to introduce notes, instead opting for the simple full stop.

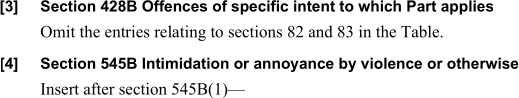

Amendments

NSW, like federal practice, places amendments in Schedules, but unlike federal legislation, does not utilise an explicit ‘activating’ section. Rather, section 64A of the Interpretation Act 1987 (NSW), inserted in 2008, provides that:

A schedule to an Act or instrument has effect according to its tenor5 when it comes into force, whether or not the Act or instrument declares that the schedule has effect.

Amendments otherwise look rather like their federal counterparts, though with somewhat wordier descriptions:

Miscellaneous

NSW, like South Australia, presents titles of legislation in italics and uses forward referencing.

While NSW legislation wins points for using simple punctuation to introduce notes, it loses many more for presenting them in a sans serif typeface inconsistent with the remainder of the document.

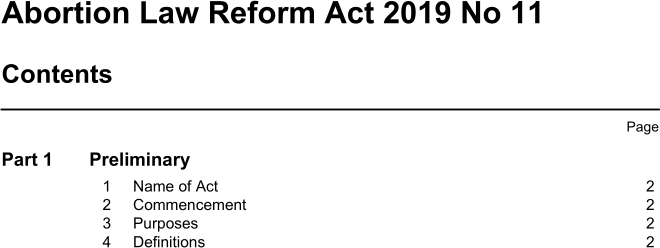

It does, however, claw some points back for having very nice tables of contents – the most aesthetically pleasing of any jurisdiction so far:

Queensland

Having discussed NSW, we turn to the Office of the Queensland Parliamentary Counsel (OQPC), whose legislation website looks and functions suspiciously similarly to the NSW website.

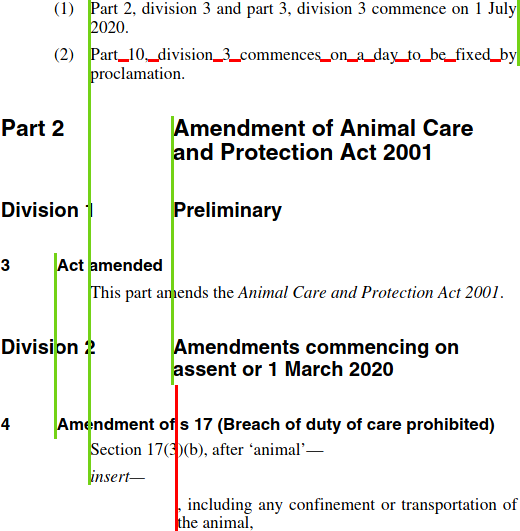

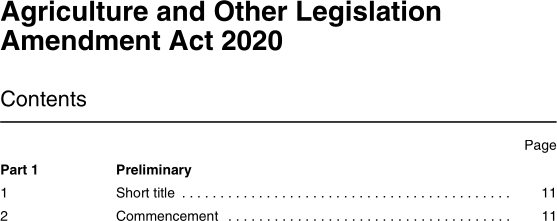

As an example, I present the Agriculture and Other Legislation Amendment Act 2020 (Qld).

Alignment

Queensland legislation sections/subsection text and numbers line up the same as NSW legislation. Curiously, though, Part numbers do not, with Part titles instead lining up somewhere apparently arbitrary in the middle of the page:

Yikes!

Like NSW, Queensland legislation text is justified, but alignment doesn't adapt well to the narrower columns relative to font size, leading to some uncomfortably large spaces between words.

Punctuation

Queensland punctuates like Victoria, with em-dashes and semicolons.

Amendments

As shown above, Queensland amendments are not in Schedules but are separated in Parts, in a format quite unlike any other jurisdiction.

An introductory provision serves as an ‘activating’ section per principal Act, while the description of each amendment places the verbs at the very end of the narration, after even any words to be omitted.

Perfectly passable, but the South Australian style probably gets the same point across more concisely.

Note that, previously, Queensland legislation used to sometimes use two em-dashes, for example, ‘insert——’. Thankfully it has now done away with such nonsense.

Miscellaneous

Queensland: Can I copy your homework?

NSW: Yeah, just change it up a bit so it doesn't look obvious you copied.

Queensland:

(Queensland follows suit behind NSW and SA with italicised titles and forward referencing.)

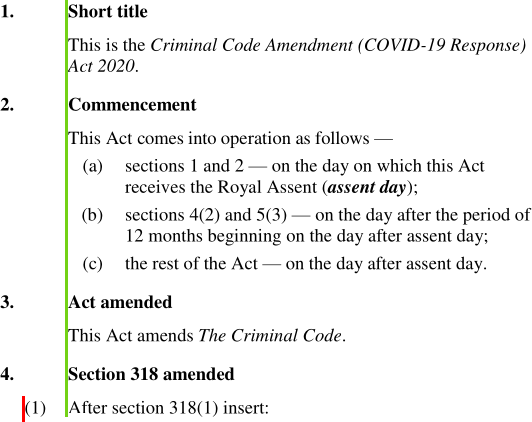

Western Australia

We complete our lap of the mainland states with Western Australia and its Parliamentary Counsel's Office.

Here is the Criminal Code Amendment (COVID-19 Response) Act 2020 (WA).

Alignment

WA legislation goes the furthest yet, aligning section text, subsection text and section headings all with each other:

As a consequence, subsection numbers are placed centrally within the left margin (though actually left aligned), and border on looking a bit funny, but probably just scrape in as not looking too bad.

Punctuation

Spaced em-dashes.

Yuck.6

Amendments

The Western Australia style of amendment pictured is the messiest yet, with the amending provisions strewn about in the main body of the Act. Like Queensland, a quasi ‘activating’ section identifies the principal Act, which WA then follows with some wordy narrative-style amendment.

Miscellaneous

WA joins the growing list of jurisdictions with italicised titles and forward referencing.

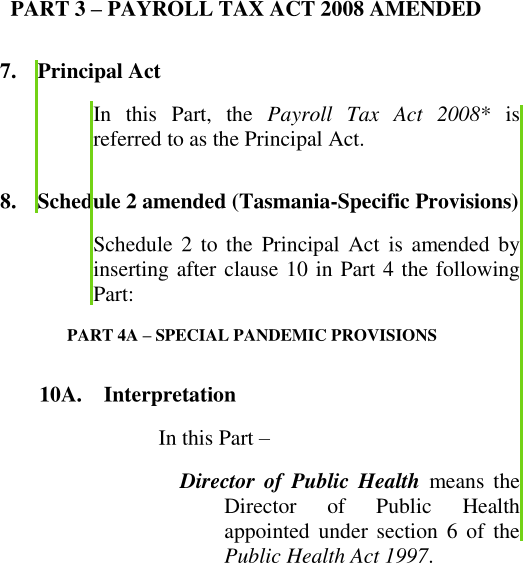

Tasmania

We complete our review of the states with Tasmania and its OPC. The Tasmanian OPC does publish some drafting manuals on its website, but these, like NSW, are fairly limited in scope.

Let's consider the Taxation and Related Legislation (Miscellaneous Amendments) Act 2020 (Tas).

Alignment

Tasmanian legislation alignment is nothing to write home about, with sections and subsections aligned, section headings aligned and Part headings centred:

Like NSW and Queensland, the text is justified, but issues with spacing are even worse than in the Queensland example:

Punctuation

Spaced en-dashes is not quite as nauseating as WA's spaced em-dashes, but is an unusual choice nonetheless.7

Amendments

Like Queensland, Tasmanian amendments are prefaced with a section identifying the principal Act, but unlike other jurisdictions adopting this approach, this section does not actually activate any amendment power – defining the principal Act is literally all that it does. As a consequence, the amending provisions still make use of longwinded narrative description, even longer than in Victoria!

Miscellaneous

No surprises here. Tasmania uses italicised titles and forward referencing.

Australian Capital Territory

We are almost done! We turn to the Australian Capital Territory and its PCO, which surprisingly has a very detailed selection of drafting guides.

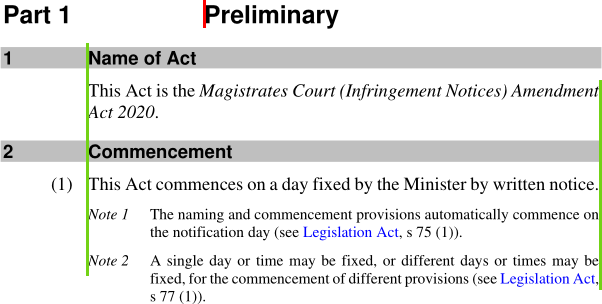

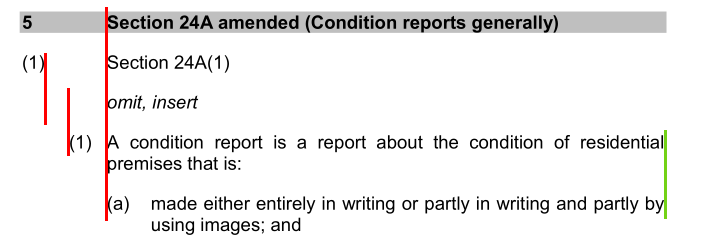

Here is the Magistrates Court (Infringement Notices) Amendment Act 2020 (ACT).

Alignment

Like WA, ACT legislation lines up the section titles, section text and subsection text, but like Queensland, the Part titles are aligned somewhere arbitrary in the middle of the page:

The justified text, however, does work well with the wide columns.

Punctuation

The ACT follows the federal OPC practice of using colons and semicolons for lists, though as shown above, notes are introduced with no punctuation at all.

Amendments

ACT amendments are very reminiscent of Queensland style, with an introductory section followed by quite abbreviated amendments:

Note, though, that both the title/summary of the amendment and the amended provision are combined in the title of the section, which probably unnecessarily inflates the length of the title.

Miscellaneous

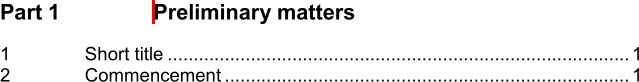

Here we see yet another ‘like NSW but slightly worse’ table of contents:

Note here that the awkward middle-of-nowhere placement of the Part heading persists even in the table of contents!

The ACT, as appears usual by now, uses italicised titles and forward referencing. However, note that the ACT places spaces between the components of cross-references (e.g. ‘section 118 (2) (b) (ii)’) – making them unnecessarily long!

Northern Territory

We complete our tour of Australia with the Northern Territory OPC.

Let's take a look at the Residential Tenancies Legislation Amendment Act 2020 (NT).

Alignment

Good lord, this is horrific!

We may have praised alignment before, but this is too much alignment! Not only are the subsections aligned, but the text of the subsection inserted by the provision is aligned at the same level as the provision itself!

There is therefore inadequate visual representation of the hierarchy of the document, not to mention the bizarre image of two ‘(1)’s in the left margin at different levels of indentation. Rather than being able to simply and naturally read left-to-right, top-to-bottom, we must instead jump sideways between the margin and the body text to figure out where we are.

At least the text is justified, whatever consolation that may be.

Punctuation

As with the ACT, the NT follows the federal practice of using colons and semicolons with lists.

Miscellaneous

The NT legislation table of contents is unlike the NSW format, but does strangely copy the ACT with its misaligned Part heading:

The NT, like the ACT, refers to legislation using italics and uses forward referencing, but unlike the ACT, does not add superfluous spaces between the components of cross-references.

Conclusion

No single jurisidction does everything perfectly, but there are some stand out contenders in each area:

- Best alignment: New South Wales. Consistent alignment across Part headings, section headings and sections/subsections makes NSW a clear winner. With just a minor tweak to line up the left edges of the Part and section headings, it would be perfect.

- Best punctuation: A combination of federal OPC/ACT/NT (colons) and NSW (commas) would maximise the friendliness of list punctuation.

- Best amendments: South Australia. Concise amending provisions combined with the flexibility to use section headings for description achieves the best of both worlds.

- Best table of contents: New South Wales. Clean and elegant. Often imitated but never duplicated.

- Best legislation titles: Everyone except Victoria. Boldface is ‘not a vibe’.

- Best cross references: Everyone except federal OPC. Reverse referencing makes sense on paper, but assumes knowledge that the reader may not have.

And to finish, I will plug legalmd, a tool I wrote to typeset pretty-looking, well-aligned PDF and RTF output from legal documents marked up in Markdown.

Footnotes

-

Not legal drafting! That would be illegal! Legal Profession Uniform Law s 10(1). ↩

-

Not out of any actual qualification, mind you – just out of being the person with the most patience for this stuff. ↩

-

Even if some of these jurisdictions have very poor taste. ↩

-

Let's just ignore the nested quotation marks. ↩

-

Not sure about the relevance of choir singers, though! ↩

-

And contrary to the Australian Government Style manual for authors, editors and printers! ↩

-

It is, of course, somewhat ironic for me to complain about spaced en-dashes while using them myself – but I am not using them at the end of lines to introduce lists! ↩